September 1987

As I was pursuing my new acting ambitions after I graduated from Michigan, I could not help but desire a taste of greatness. I surely had much to prove to the world and myself, as any graduate might with bright hopes for their future. The idea of being a great actor, when I chose acting, superceded the idea of being a “good actor” or a “good anything” for that fact. Who wants to be good when they can be great?

My father had instilled that desire for greatness, not by beating it into my head, but by imbuing it through rewarding good actions. A winning touchdown pass that I threw as an 8th grade football player in the last moments of a football game was a defining moment that said to me such feelings were worth pursuing. How wonderful were the rewards that came from winning and/or receiving that special something from Dad, even if it was just a pat on the back and encouraging words like “Great job.”

After that ecstatic junior high school football victory, my father rewarded me with a twenty dollar bill and treated me and my friends to pizza. Extrinsic rewards worked well for me as I found that pleasing my father always worked to my benefit like following the law pleases our justice system.

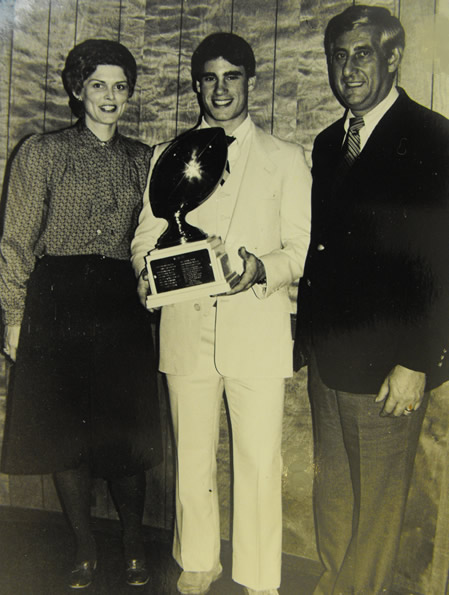

When I received a trophy for Most Valuable Player on the high school football team several years later in 1981, I realized the road was few and far between those fleeting moments of great, heroic acts like throwing winning touchdown passes in the last seconds of a game. Unfortunately, there weren’t too many moments like that day. Dad reminded me that the rewards of glory are few and far between and not to count on them for the fulfillment of one’s destiny, pointing to a few former high school star athletes from his hometown who graduated and were still hanging out on a park bench reminiscing about their glory days.

My glory was a different kind of glory, but more sustaining. I learned it was through steady discipline, consistent action and riding the ups and downs of the rocky road ahead, for better or worse, over a long period of time, that was the way to greatness, if it were to be achieved at all. Sticking to it, like my father had done to become a doctor, was the way to a more successful future. Over the years Dad would point to that trophy, encouraging me that I could do anything if I set my mind to it.

This “greatness” thing was hanging over me like a huge cloud that defined my being. That I had to be something was culturally rooted in such films like On the Waterfront with Marlon Brando’s character telling his brother about his desire to be a contender or Rocky Balboa waking up one day to realize he’s not lived up to his potential; in sports with role models like Michael Jordan winning championship games for the Chicago Bulls and John Elway winning two Super Bowls in the twilight of his career; or maybe it came from just being an American where we are instilled with the idea that we are the greatest nation on earth. Wherever this idea of greatness took root, from great civilizations of World History to our great forefathers of America or in the great characters of the plays of William Shakespeare, the bug bit me hard and I wanted something more out of my life than mediocrity.

My father must have picked up on my anxiety when I told him about this desire for greatness.

Dear George,

To say “I want to be great” (at what I do with my life) is an admiral character trait. Great for what? Glory? What will be the relevance of such greatness? How can one’s life be relevant? Relevance is the oft forgotten attribute missing in many so-called greats, in the tragic heroes and their flaws.

Greatness is too broad a term. All Ruth’s homeruns, the many movies of a Woody Allen. So many famous people, so many accolades. Yet, each must ask despite his so called greatness, what is it that makes my life relevant.

Each of us has a capacity for relevance because relevance relates usually to the society, friends and family around us.

So after one becomes great, it is also important that such a life is indeed relevant. And should it fail to be relevant, such a life will be like a very beautiful but empty cup. It is great for its beauty, and empty of relevance. So if you do not have enough to strive for, I have reminded you of this other burden of relevance. This, however, is an easier more natural one because it is an easy habit to get into and measure everyday.

If a thing is irrelevant to you, then it must be avoided. Everyone’s life can be relevant and therefore great.

My father, as much as he talked about “greatness,” through his heroes like Winston Churchill and other political leaders, contemporary and historical, reiterated the necessity of relevance over the course of my life. When I got my first teaching position as a social studies teacher at a high school in Newark, NJ from 1990 to 1992, I realized that the way to my students’ hearts and minds was in making subject matter relevant. Textbooks that were dry coupled with tasks that were boring had very little relevance to the lives of black Americans, forcing me to find other ways to reach them. Spending extra hours at the library to learn African-American history and their key role models throughout history would bring greater esteem upon me than almost anything I had done in my life, including winning a football trophy.

I would become a much better teacher when I worked on the attribute of becoming relevant rather than focusing on greatness.

At the end of my father’s letter he advised me to keep writing and to keep a diary, which he had first encouraged when I went to Japan. It was an affirmation that he asserted throughout my life and he really did help me become a better writer, first through the confidence I gained in letters I wrote him and the several daily journals I kept for myself over several years and then later when I became a graduate student of writing, an English teacher and practicing writer myself.

I would not make the connection until much later in life about the influence of those letters - that through them, I was preparing myself for something I could not foresee. Where it was all leading, I would not know. But writing was my way of discovering my place in the world and my father gave me this confidence. Later, my knowledge of writing, both through the daily habit of doing it and the formal education I would receive would become the basis for more relevant acts in and out of the classroom.

Our lives are governed much more by positive influences than we may realize. It takes time to discover the thread of our existence and the reason why we are here on this planet and how it is shaped by very special role models such as people like my father or teachers in our schools and the great people who serve, in all walks of life, to inspire us through their presence.

The lesson of living a life of relevance would continue to play out over the next 25 years of my life until my father’s death. Nor would that lesson diminish with his passing but rather grow stronger like an orchestra band beating a steady drum to the Stars and Stripes Forever.