Arts & Entertainment

Arts & Entertainment

Exploring Creative Process with Plein Air Painters

- Details

- Published: 10 August 2010 10 August 2010

In a hundred years, how will the world view your work? What will they see in that field you have rendered, the barn you have sketched, the poplar trees you have captured? And what will that tell them about their own world?

One Sunday in July, I spent half the day with the Wallkill River School Plein Air Painters, with the objective of looking at the creative process. My journey began with a camera, notepad and pen, tools that would help transform my ideas into something whole.

Painting at different locations throughout Orange County over the course of the summer, the painters converged at Keith Stewart’s organic farm in Greenville, NY. Flavia Bacarella, Keith’s wife and an artist, invited me to attend the workshop. I went with an open mind, not sure what to expect, nor what kind of outcome I would produce.

It had rained the previous day, so when I arrived to the farm, with over 100 varieties of fruits and vegetables, the land and its vegetation was perked up, looking lush and verdant. Many of the artists had already established a spot for themselves; there were easels and canvases propped up in every direction. I wrote in my notebook. There is something that attracts our eye to put us in our own very special spot.

For the plein air painter, finding a spot is the starting point for creating. What is that something that attracts us to where we ultimately station ourselves? Is it a random, unconscious act or is it deliberated upon, our eye drawn to a theme or a point of interest or something that represents for us a novel interest in which we can add something new to our dimension of living?

For the plein air painter, finding a spot is the starting point for creating. What is that something that attracts us to where we ultimately station ourselves? Is it a random, unconscious act or is it deliberated upon, our eye drawn to a theme or a point of interest or something that represents for us a novel interest in which we can add something new to our dimension of living?

One of my goals was to spend a little time with the artists and watch the development of their work. I added more notes in my book. Somehow we begin with our ideas and we take those ideas and nurture them. It’s really a very simple process amidst a complex act that requires skill, experience and the desire to see it through.

My other intention for the day was to write a couple of poems, inspired by my own observation. I did not know when these poems would reveal themselves to me, but I had faith they would.

I further wrote in my journal: The field does not grow abundant fruit and vegetables without the guiding hand of someone to make it happen. To me, this is what it means to cultivate. It means to shape, to nurture, to help bring into existence an idea with potential and raise it into its fullest manifestation. Time is always a factor in the unfolding of events.

I somehow had to become present – to be still when I needed to be still and to move when I needed to move. What is that force that guides us? Is it something Taoist, when you are out in nature under these circumstances and you are moved like the stream is moved, like the wind that blows across your face from nowhere? Creation certainly must account for the ebb and flow of natural occurrences.

At first I observed a demonstration in technique, with the speaker discussing her plein air painting which was set on an easel facing the landscape she had been working on. I put my head down and listened while taking notes. What you might have heard would include advice on capturing the landscaped elements such as the far off hills, the clouds, the contours of a ridge, the horizon, rocks, etc. And some advice about taking liberties with your view. The instructor said, “Give it a thin layer now and then get the details later.” She had been working on the painting earlier, so it was near completion. She gave us an example of adding some final details. How true it is that our creative acts allow for the addition of details. As you have layered and layered, those new details become layers for newer additions.

At first I observed a demonstration in technique, with the speaker discussing her plein air painting which was set on an easel facing the landscape she had been working on. I put my head down and listened while taking notes. What you might have heard would include advice on capturing the landscaped elements such as the far off hills, the clouds, the contours of a ridge, the horizon, rocks, etc. And some advice about taking liberties with your view. The instructor said, “Give it a thin layer now and then get the details later.” She had been working on the painting earlier, so it was near completion. She gave us an example of adding some final details. How true it is that our creative acts allow for the addition of details. As you have layered and layered, those new details become layers for newer additions.

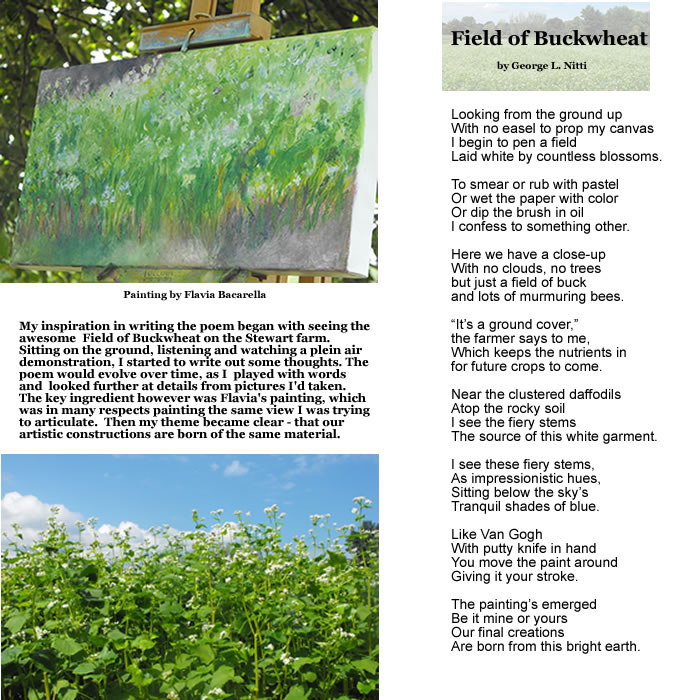

Then my first poem revealed itself. I was looking at a close-up of a field of buckwheat, mesmerized by the robust activity of bees, which were producing this murmuring din that was enchanting to listen to. I sat there for twenty minutes, looking intensively at my subject matter, as I knew I needed to capture details.

However, I did get stuck after twenty minutes. Later on, Lynwa, one of the artists, informed me that when she got stuck, she moved around and checked out what other artists were doing. "Take a break," she said and "look at other things." She was working on a watercolor, finding plein air painting a challenge because of how quickly her watercolors were drying.

I did not like the discipline of imposing a time limit on my artistic act anyway. I knew that I was here for other reasons and that writing a poem was only part of my larger objective. I would have to get back to the poem later. Yet I knew one thing: I was committed to writing it. The seed was planted. The poem was ready to be written. It would just be a matter of time. First I needed to move around and get other perspectives. Ah, I was in the spirit of creating.

After the group instruction was over, the artists returned to their easels'. As I met with several of them, I realized that each artist arrives at an end point through their own means. For me, getting to the end, in part, is a matter of will – yet at its core, has a seed that’s already been planted, one that sprouts and grows with each step, one that develops, one that matures, only when cultivated through some kind of process. That's what I call creativity.

The several plein air painters that I spoke to helped inform the creative process and inspired me along my own personal journey to have a meaningful experience en plein air, one in which I would become a creator myself. And as such, I realized I was the one responsible for shaping it into a meaningful event.

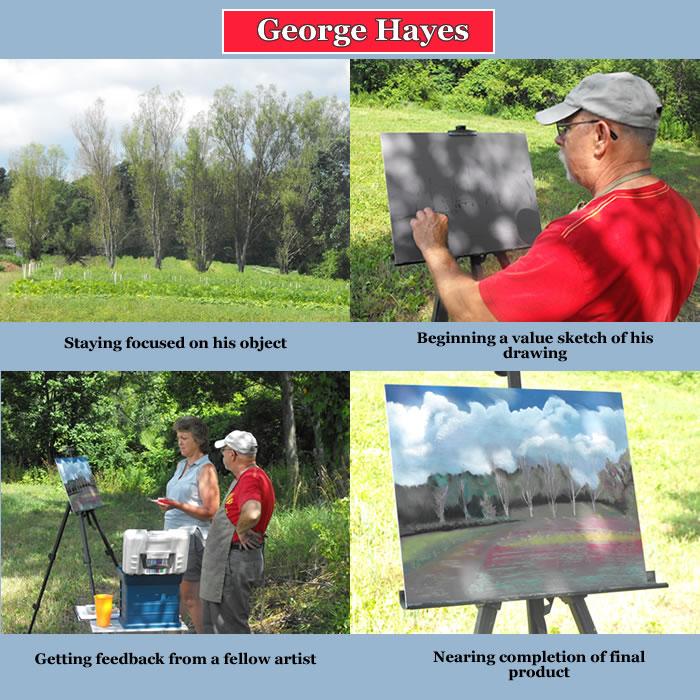

George Hayes, one of the first artists I spoke to, was working on a value sketch that provided him with an outline that would help guide him through his process. He told me he spends about ten to fifteen minutes working on it before he even begins to draw with his pastels.

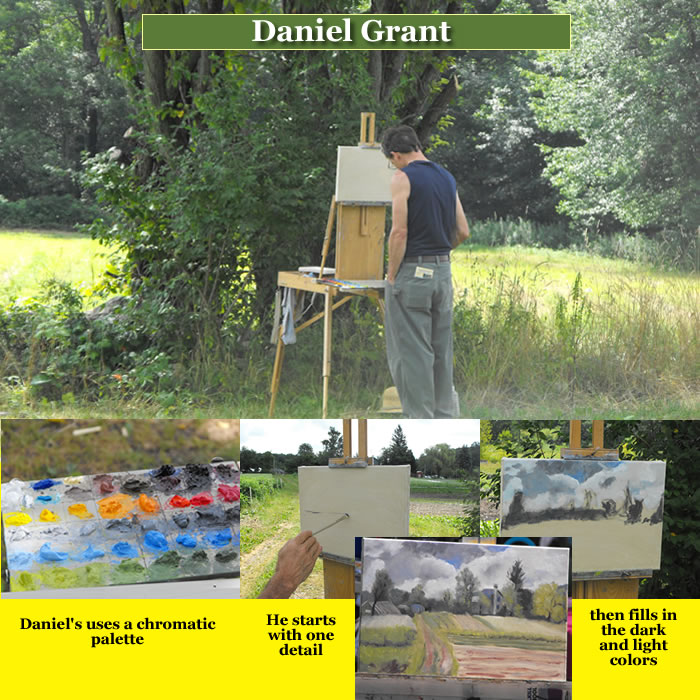

Daniel Grant, by contrast, who works in oils and learned to use a chromatic palette at the Ridgewood Art Institute, told me that he begins with one detail and works around it, adding the dark and light colors as he goes along, working without a plan per se, such as a value sketch. Yet he achieves the same result – a finished painting.

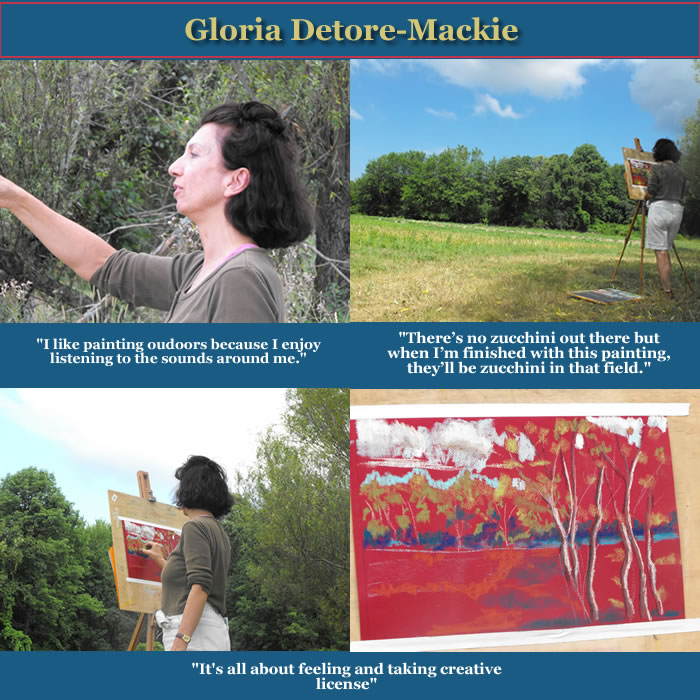

Gloria Detore–Mackie, who also works in pastels, was comfortable manipulating reality, counterintuitive to some who aim to capture exactly what is there. The question of when and how to fabricate reality is one of the keys to creating art.

My conversation with Gloria inspired my second poem, which drew on the sounds I experienced with her during the moments we spent together.

Sans the Sound

Chirping birds, motoring cars, whirring bees, rustling grass, stomping boot, shuffling

feet, thudding branch, and breath of air from chalky dust of pastels brushed with hand –

these are the sounds unfolding to my ear.

I wish I could record and playback what I hear

while you look at my finished landscape.

Through these reds, whites and olive greens

That forged the trees and clouds beyond,

sans the sound

somehow this painting seems incomplete.

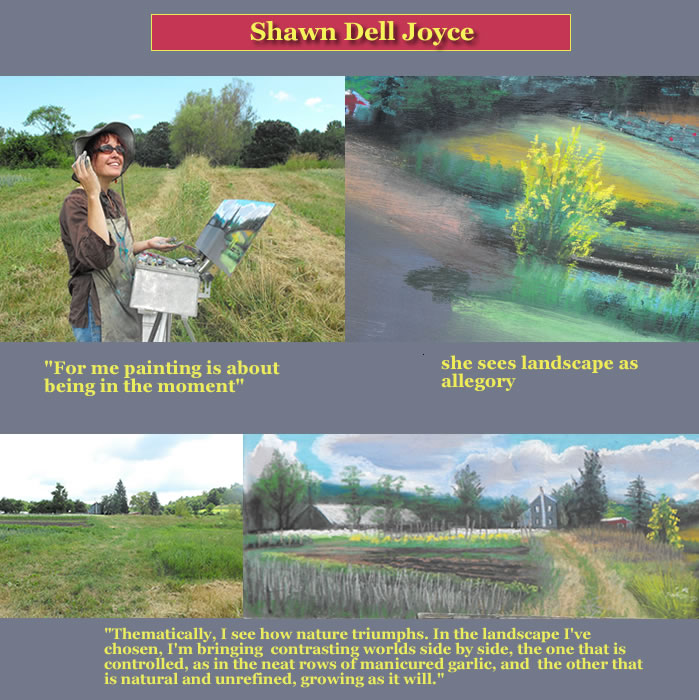

Shawn Dell Joyce, founding member of the Wallkill River School, talked to me about her process of working with theme while seeing landscape as allegory.

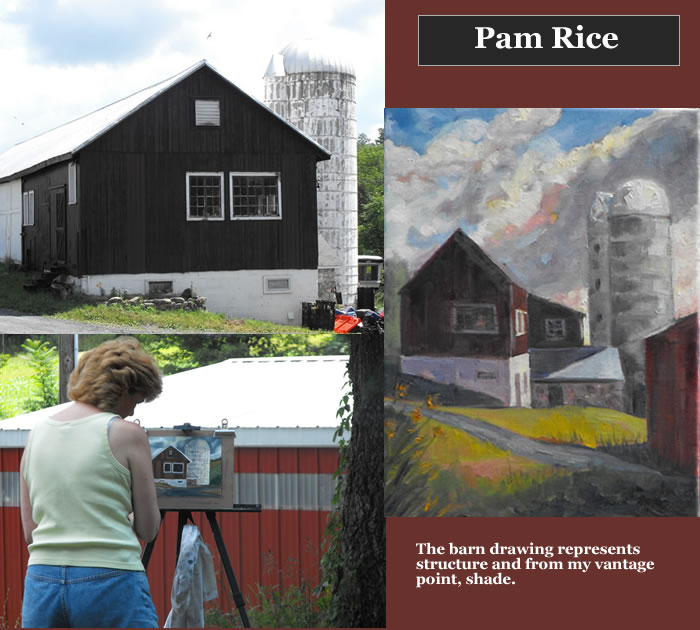

When I approached Pam Rice, she was just finishing up her painting. I did not say much to her, but merely admired how accurately she had rendered the shape of the barn in only two short hours.

As the time was winding down, I visited Flavia to see how she was doing with her painting. I discovered she was working on an impressionistic rendering of the field of buckwheat, almost from the same view I was looking at the field - a close-up shot - and I got another bit of inspiration. She told me that art was a psychological battle for her and that the creative process involved some degree of suffering. Looking at my own process, especially my poem, "The Field of Buckwheat," I understood her creative struggle to come to resolution. It was so hard for me too.

At the end of the two hours, all of the artists were brought together to share their work over lunch. It was interesting to see the diversity of art, in style, form and medium. Shooting more pictures, not really knowing how I was going to use my material, I trusted everything was going to come together.

It wasn’t until I got home and sat with my project for several weeks before I attempted to make sense of my experience. The poem, however, was finished, as I was eager to get it done when I got home. But in truth, the poem was never really finished, because through each reading, I found something to change, add or delete. Everything I used – the poem, the pictures, the scrawled notes I had taken quoting various artists – everything that I had put down in my little notebook could become a valuable source for developing ideas.

Although I was invited by Shawn to partake in another week of Plein Air Painting and to take up painting myself, I knew I didn't have the time this month. My day out with the Plein Air Painters was more than just a half day event though. It was a multi-layered process in which I would continue to add more detail over time.

My end game was to write this story. But first I wanted to have a meaningful experience. It took me several weeks, and now that I look back over my creation, I feel I've accomplished that. The poems are finished and I'm more attuned to the creative process. It's a continual unfolding. And when I put down my pen, even then, the act of creation continues to pursue me to some new destination.

Pilgrimage to Pacem in Terris

- Details

- Published: 07 January 2010 07 January 2010

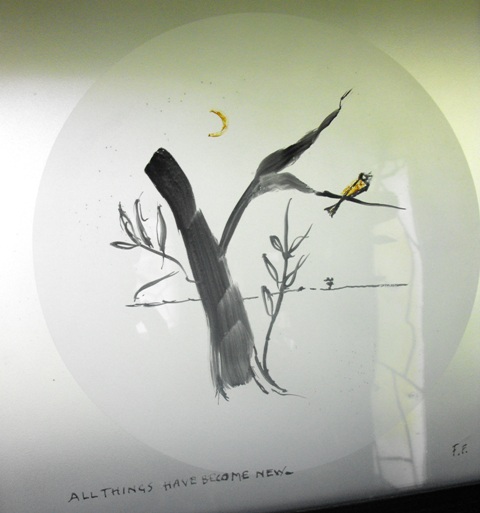

"However far you may walk, every pilgrimage is a safari into your own dark interior, an inner journey. For pilgrimages belong to the inner world, to that realm called "the religious." Frederick Franck, Art as a Way: A Return to Spiritual Roots

The life of Frederick Franck is well documented, but one that takes time to sift through, containing many layers, like any rich life. To unearth it, one must dig into the terrain of his world - carefully, slowly, persistently. His story, like any classic, never grows tired, as there is something new to discover upon each return.

On a midsummer’s day, I begin my pilgrimage to Pacem in Terris, a place that Frederick Franck and his wife Claske transformed into one of Warwick's crown jewels. Located off of Covered Bridge Road in Warwick, NY, Pacem in Terris, meaning "Peace on Earth" was a home fit to be condemned when first settled by the Franck's. Frederick writes in Pacem in Terris: A Love Story: "Contractors we consulted immediately diagnosed it as a terminal case, only fit to be torn down at once..." But instead of tearing down, Frederick and Claske rebuilt, resurrecting Pacem from the rubble with the help of a dutch carpenter named Bert Willemse.

Fine Arts, Finding Balance and Family Life with Artists Janet and Louis Fatta

- Details

- Published: 05 May 2009 05 May 2009

Warwick artists Janet and Louis Fatta determined early on that they would pursue their passion parallel to their busy family life. Janet, a painter, and Louis, a metal sculptor, met at Pratt Institute as students, married, became parents, and with clear vision and a few faithful relatives and friends built a classic pole barn on their property to separate the crayons from the oils and the clothing iron from the anvil.

Janet works in the large loft space, where abundant northern light enters and falls on her canvases. The products of her skill and expertise are everywhere. When not giving lessons, she works in alternating mediums according to her mood on any given day. Subjects range from perfectly rendered nude charcoals to candy colored oil abstracts (inspired by a trip to the Museum of Natural History’s Cosmic Collision Space Show). Annual Christmas portraits of the extended family-- one all in shades of blue, a tribute to her appreciation of Picasso’s Blue Period, depict the large extended family’s poignant idiosyncrasies as they gather around the holiday table.

Janet works in the large loft space, where abundant northern light enters and falls on her canvases. The products of her skill and expertise are everywhere. When not giving lessons, she works in alternating mediums according to her mood on any given day. Subjects range from perfectly rendered nude charcoals to candy colored oil abstracts (inspired by a trip to the Museum of Natural History’s Cosmic Collision Space Show). Annual Christmas portraits of the extended family-- one all in shades of blue, a tribute to her appreciation of Picasso’s Blue Period, depict the large extended family’s poignant idiosyncrasies as they gather around the holiday table.

In the middle of the studio on a high stool, sits a lemon on a simply patterned plate. Its brilliant still-life likeness mirrors back from a nearby easel. When asked, “Why a lemon?” she recalls the bagful that she bought but couldn’t use up. Then with a nod to creative license she shrugs, “Because it was there. And I like lemons.” Janet’s talent is at once bold, yet sweetly unsung.

In addition to the routine interruptions these two dedicated artists face as parents, they admit that it is a challenge to contend with each other’s coveted time in the studio. They must constantly defer to fairness as one takes up house duty while the other grabs a block of time in the studio. They smile in agreement about the tension, but there is no complaining. They are obviously at peace with their choices.

Louis is an art teacher in Rockland County by day, and an actively working sculptor at every other available opportunity. The barn’s ground level is his domain. It sports its original hard packed dirt floor and in the center, tool of his trade, a welding machine. The doors face the woods and not fifty feet out, a steep ravine drops down to a noisy little brook. Many of his pieces are scattered around outside, seemingly by random among overgrown grasses, weeds and trees. Pitted by rust and weather, they appear at home: vestiges of urban energy juxtaposed with shapes of nature, like omens for seeing eyes. As Fatta explains his artistic objectives it becomes clear that the apparent randomness is intended-- implying man’s cavalier footprint on a vulnerable earth.

Fatta chooses a few profoundly representative shapes including the automobile, the raven and the ant, stacked in varied combination, as totems to humanity’s heedless stamp and nature’s relentless capacity to compensate. Cut in minimal silhouette, their relationships become intuitively apparent. The automobile, catapult to the industrial revolution. The raven, scavenger/sentinel. The ant, carrion consumer. Wrought in welded steel they stand, mute tattletales on civilization’s successes and its sins.

One of Fatta’s major influences is Romanian sculptor Constantin Bancusi, whose non-literal representations reflect “… not the outer form but the idea, the essence of things…” and the impossibility “for anyone to express anything essentially real by imitating its exterior surface.” This ideology shows up for instance, in the semi circle spaces where wheels would fit under cuts that form the automobile bumpers. No motion here. Just the mind of motion. Or again, in the relatively realistic ant set on small garage door wheels. Ants don’t skate. But they don’t stop either. Like commuters in cars.

As recurring imagery is manipulated, new images are introduced, such as a rectangular skyscraper among tall wavy weeds. And new messages of growth, decay, recovery and resolution materialize.This layering and reworking is a little like Janet and Louis and their kids and their dog. Only their skyscraper looks like a pole barn. Their car is an SUV. And you might find a few ants among the cookie crumbs on the counter. All a cheerful totem to the grounded artist’s life.

ReeAnne Davies is a freelance writer, having worked in educational publishing for many years, in both editorial and administrative positions. A mother of five, she can be found reading contemporary literature, hiking the Appalachian Trail, studying ancient scripture or pondering the direction of American culture and politics. ReeAnne can be reached via email at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..